B-cell Lymphomas

Precursor B-cell Lymphomas

Mature B-cell Lymphomas

- Follicular lymphoma

- Mantle cell lymphoma

- Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

- Burkitt’s lymphoma

- Marginal zone lymphomas

- Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia)

T-cell Lymphomas

Precursor T-cell Lymphomas

Mature T-cell Lymphomas

- Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma

- Anaplastic large cell lymphoma

- Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (including mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome)

- Peripheral T-cell lymphomas:

B-cell Lymphomas

Precursor B-cell Lymphomas

Precursor B-cell Lymphoblastic Leukemia/Lymphoma

What is it?

- A precursor B-cell, called a B-cell lymphoblast, is an immature lymphocyte that is eventually destined to become a mature B-cell. It is this cell that becomes cancerous in precursor B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma.

- Precursor B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma is a type of aggressive NHL that occurs mainly in children and adolescents, with two thirds of patients being male. A second peak of occurrence happens later in life in patients over 40 years of age.

- Lymphoblastic cancers are classified as either lymphoblastic leukemias (called acute lymphoblastic leukemia or ALL) or lymphoblastic lymphomas. Both are cancers of immature lymphocytes with the major differences illustrated in the following table:

Lymphoblastic Leukemia Lymphoblastic Lymphoma Type of lymphocyte most commonly affected B-cells T-cells Where the cancer is located Bloodstream Lymph nodes - The majority of precursor B-cell cancers are leukemias, which are far more common than precursor B-cell lymphomas.

What are the symptoms?

- The most common symptoms include pallor (paleness of skin), fatigue, bleeding, fever and infections.

- When a blood test is performed and blood cells are counted, red blood cells and platelets are usually lower than normal, while white blood cells may be low, normal or high in the bloodstream (although they are abnormal in the bone marrow).

- At the time of diagnosis other sites outside of the lymph nodes may also be affected and may cause symptoms such as swollen lymph nodes, enlarged liver or spleen, neurological disturbances, enlargement of testicles in men or skin involvement.

How is it diagnosed?

The diagnosis is usually made by bone marrow biopsy. A sample of bone marrow is removed from the patient and examined under a microscope. This usually shows high numbers of cancerous B-cell lymphoblasts.

How is it treated?

- The treatment of patients with precursor B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma involves combination chemotherapy, which is chemotherapy used in combination with different drugs.

- The overall cure rate in children is 85%, while about 50% of adults remain disease-free for long periods of time. In patients whose disease is confined to lymph nodes, a high cure rate is often possible.

Mature B-cell Lymphomas

Follicular Lymphoma

What is it?

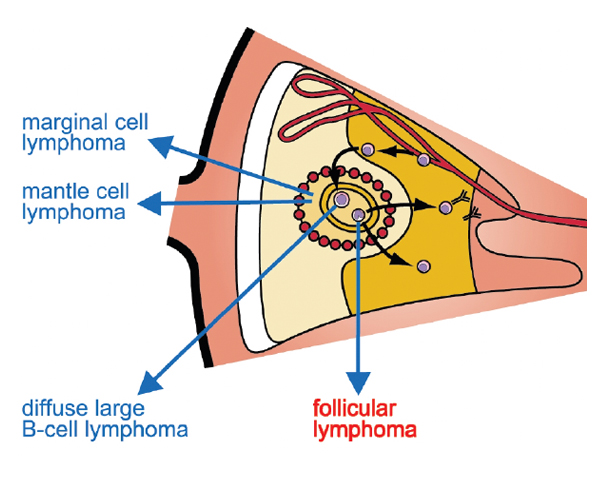

- Follicular lymphoma is a B-cell lymphoma where the tumour cells often create a circular or follicular pattern when viewed under the microscope.

- Follicular lymphoma is the most common subtype of indolent (slow-growing) NHL, comprising 20% to 30% of all NHLs.

- Follicular lymphoma typically affects middle-aged or older adults.

- Follicular lymphomas arise from B-lymphocytes, and as such are referred to as B-cell lymphomas.

- Like most indolent lymphomas, people diagnosed with follicular lymphoma usually have tumours in many parts of the body at the time of diagnosis.

- Follicular lymphomas can transform into a more aggressive form of NHL, usually a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

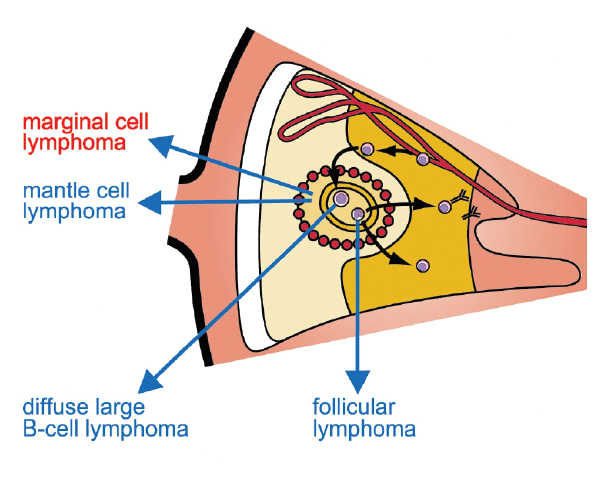

A section of a lymph node showing the origin of follicular lymphoma

What are the symptoms?

- The most common sign of follicular NHL is painless swelling in the lymph nodes of the neck, armpit or groin.

- Sometimes more than one group of nodes are affected.

- How is it diagnosed?

- The diagnosis of follicular NHL is confirmed by a lymph node biopsy. To do this a sample of the lymph node is removed and examined under a microscope to check for cancerous cells.

- Other tests including X-rays, bone marrow biopsy, CT scans and blood tests may also be performed.

- In the event that follicular NHL transforms to a more aggressive form of NHL, the NHL must then be re-diagnosed and a second lymph node biopsy or other tests may be required.

How is it treated?

- Treatment for follicular lymphoma depends on the stage of the lymphoma.

- Patients who are diagnosed at an early stage (stage I or II) may receive the watchful waiting approach (no treatment), radiation therapy or chemotherapy. Local radiation therapy often produces excellent results, with remissions lasting longer than 10 years in 50% of patients.

- Patients who are at a later disease stage (stage III or IV) at the time of diagnosis but who are not experiencing symptoms may receive no treatment (watchful waiting approach) with very close monitoring.

- Once the need for treatment arises the most common treatments include:

- Single-agent chemotherapy (e.g., chlorambucil) or combination chemotherapy (e.g., CVP or CHOP).

- Rituximab (Rituxan®), a monoclonal antibody, is often used either alone or in combination with chemotherapy.

- Radiation therapy.

- Radioimmunotherapy, including medications such as tositumomab (Bexxar®) and ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin®), may also be used.

- Prolonged treatment with Rituxan®, called Rituxan® maintenance therapy, has recently been approved by Health Canada for the treatment of patients with follicular NHL who have responded to their initial treatment. This means that patients who have received treatment for follicular lymphoma and have achieved remission (complete or partial remission) may benefit from prolonged administration with Rituxan® (generally administered every three months for a period of two years). Rituxan® maintenance therapy has been shown to sustain the response obtained from the initial therapy and may improve survival for patients with follicular lymphoma.

- Follicular NHL usually responds quite well to chemotherapy. However, there is a risk that it may return in future years. At that time, treatment is given again and the disease can again be brought under control. This pattern may repeat itself over many years.

Mantle Cell Lymphoma

What is it?

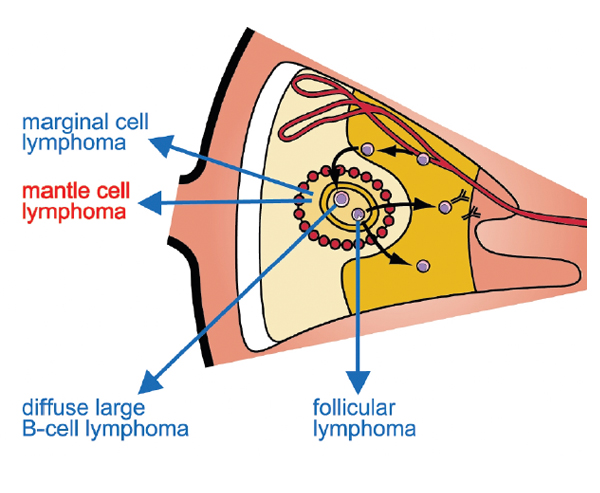

- Mantle cell lymphoma is a type of aggressive B-cell lymphoma that most commonly affects men over the age of 50 years, although it can affect women.

- It is relatively uncommon and accounts for approximately 5% to 10% of all NHL cases.

A section of a lymph node showing the origin of mantle cell lymphoma

What are the symptoms?

- The most common symptom is a painless swelling in the neck, armpit or groin, caused by enlarged lymph nodes. Often lymph nodes in more than one area of the body are affected. Splenomegaly (enlargement of the spleen) is relatively frequent and may cause patients to feel fullness in the abdomen after eating only small amounts.

- Mantle cell lymphoma is aggressive and may spread to other organs in the body, including the bone marrow, spleen and liver. It can also spread to the stomach or digestive tract.

How is it diagnosed?

- The disease is usually widespread at the time of diagnosis.

- The diagnosis of mantle cell lymphoma is confirmed by a lymph node biopsy. A sample of the lymph node is removed and examined under a microscope to check for cancer cells.

- Other tests including X-rays, bone marrow biopsy, CT scans and blood tests may also be performed.

How is it treated?

- Mantle cell lymphoma is usually treated with combination chemotherapy, or combination chemotherapy plus rituximab (Rituxan®). This includes regimens such as:

- CHOP chemotherapy or Rituxan® plus CHOP chemotherapy. CHOP chemotherapy is a combination of chemotherapy drugs including cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone.

- Mantle cell lymphoma can also be treated with radiation therapy, stem-cell transplant and other newer treatments.

- Treatment is often initially successful. However, mantle cell lymphoma frequently relapses. While newer treatments have been developed to treat this type of lymphoma, patients with mantle cell lymphoma are often encouraged to participate in clinical trials so they can receive newer treatments that are not yet on the market.

Burkitt’s Lymphoma

What is it?

- Burkitt’s lymphoma is a very aggressive (high-grade) form of NHL and commonly affects both children and adults, with males being affected more frequently than females.

- The disease can be associated with viral infection such as the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and the Epstein-Barr virus.

- Burkitt’s lymphoma accounts for 30% to 40% of all childhood lymphomas and occurs in children between the ages of five and 10 years and in adults between the ages of 30 and 50 years.

What are the symptoms?

- The most common symptoms of Burkitt’s lymphoma are swollen lymph nodes and abdominal swelling.

- Burkitt’s lymphoma may also affect other organs such as the eyes, ovaries, kidneys, central nervous system and glandular tissue such as breast, thyroid or tonsil. Disease in these organs may cause variable symptoms.

How is it diagnosed?

- The diagnosis of Burkitt’s lymphoma is confirmed by a lymph node biopsy. A sample of the lymph node is removed and examined under a microscope where it is checked for cancerous cells.

- Other tests including X-rays, bone marrow biopsy, CT scans and blood tests may also be performed.

How is it treated?

- Although Burkitt’s lymphoma has a very aggressive course, survival rates with treatment are approximately 80%.

- The most common treatment for Burkitt’s lymphoma is intensive chemotherapy with drugs such as cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, methotrexate, cytarabine, ifosfamide and etoposide.

- Other treatments include monoclonal antibody therapy and stem-cell transplants.

Marginal Zone Lymphomas

- Marginal zone lymphomas are a type of indolent B-cell lymphoma that account for approximately 10% of all NHL cases.

- Marginal zone lymphomas can be categorized according to the area affected:

- Mucosa-associated lymphatic tissue (called MALT lymphoma), which can affect the gastrointestinal tract, eyes, thyroid, salivary glands, bladder, kidney, lungs, neurological system or skin

- Spleen (called splenic marginal zone B-cell lymphoma)

- Lymph nodes (called nodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma).

- The average age of diagnosis of marginal zone lymphoma is 65 years, although MALT lymphomas can occur earlier.

A section of a lymph node showing the origin of marginal zone lymphomas

Extranodal Marginal Zone B-cell Lymphoma of Mucosa-Associated

Lymphatic Tissue (MALT) Type

What is it?

- MALT lymphomas mainly occur outside the lymph nodes, in extranodal sites.

- Many patients who develop this type of NHL usually have a separate autoimmune disease or inflammatory process such as Sjögren’s syndrome (salivary gland MALT), Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (thyroid MALT), or Helicobacter gastritis (gastric MALT).

What are the symptoms?

Patients may have symptoms such as upper abdominal discomfort or local symptoms relating to where the disease occurs.

How is it diagnosed?

The diagnosis is made by biopsy of the tumour and examination of the cells by a specialized doctor called a hematopathologist. The diagnosis is confirmed by the infiltration of small B-cells.

How is it treated?

- Extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT type is often curable when localized.

- Surgery is not often a common treatment for NHL. However, in this particular type of NHL, local therapies such as radiation therapy or surgery can be curative.

- Patients with gastric MALT lymphomas who are infected with a bacteria called Helicobacter pylori can achieve lengthy remission in the majority of cases once the infection is effectively treated with antibiotics.

- Patients who present with more extensive disease are usually treated with single-agent chemotherapy such as chlorambucil or combination chemotherapy.

- In some cases this type of NHL can transform into an aggressive form of NHL called diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). The standard therapy for DLBCL is CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab (Rituxan®) (a monoclonal antibody).

Splenic Marginal Zone Lymphoma (SMZL)

What is it?

- SMZL is a type of indolent B-cell NHL that predominantly involves the spleen. The spleen is located in the upper left corner of the abdomen.

- SMZL is a rare type of lymphoma accounting for less than 1% of all NHLs.

- It most commonly occurs in adults and is slightly more frequent in women than in men.

What are the symptoms?

- Symptoms do not normally appear until years after the disease has begun.

- The most common symptom is an enlarged spleen (splenomegaly). Unlike many other NHLs, there are normally no swollen lymph nodes.

- There is usually involvement of the peripheral blood and bone marrow at the time of diagnosis. This involvement will be evident on laboratory tests with the only symptom being fatigue.

How is it diagnosed?

Diagnosis is based on identification of the cell type in conjunction with the typical clinical findings. A biopsy of the bone marrow can often yield the diagnosis, however, removal of the spleen (splenectomy) is occasionally required for tissue examination.

How is it treated?

A number of different approaches may be taken with SMZL, including:

- Watchful waiting approach (common in many indolent lymphomas)

- Removal of the spleen (splenectomy)

- Radiation therapy

- Chemotherapy

- Biologic therapies with drugs such as rituximab (Rituxan®) (a monoclonal antibody).

Nodal Marginal Zone Lymphoma (NMZL)

What is it?

- NMZL is a type of indolent B-cell NHL that is primarily confined to the lymph nodes.

- It is a rare form of lymphoma, accounting for only 1% to 3% of all NHL cases.

What are the symptoms?

The most common symptom of NMZL is a painless swelling in the neck, armpit or groin caused by enlarged lymph nodes. Sometimes more than one group of nodes are affected.

How is it diagnosed?

NMZL is diagnosed by lymph node biopsy. A section of the lymph node is surgically removed and examined under a microscope.

How is it treated?

The most common treatments for NMZL include:

- Watchful waiting approach

- Radiation therapy

- Chemotherapy with medications such as chlorambucil or fludarabine.

- Rituximab (Rituxan®) (a monoclonal antibody) is often used in combination with chemotherapy.

Lymphoplasmacytic Lymphoma (Also Called Waldenstrom’s Macroglobulinemia or Immunocytoma)

What is it?

- Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma is a rare form of B-cell lymphoma, making up 1% to 2% of all NHL cases.

- It typically affects older adults and has a slow-growing, indolent course.

- It arises from mature B-cells that are on their way to developing into plasma cells (B-cells that produce antibodies). In this type of lymphoma an overproduction of a certain type of antibody, called IgM, can occur.

- When this IgM antibody is present, the lymphoma is also referred to as Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia. A large amount of IgM in the bloodstream causes thickening (hyperviscosity) of the blood.

What are the symptoms?

- Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma normally develops over a long period of time. Symptoms are not usually very obvious and as such, the disease is often found by chance when getting a routine blood test or an examination for some other reason.

- Some symptoms can include weakness, fatigue and bruising as a result of altered blood cell levels. Lymph nodes may be enlarged, as may the liver and spleen.

- Because there may be a thickening of the blood when the IgM antibody is present, this can cause other symptoms including sight problems, headaches, hearing loss or confusion.

How is it diagnosed?

- This type of NHL is usually suspected after an abnormal blood test. Other tests that help confirm the diagnosis include:

- A bone marrow biopsy to determine the exact type of NHL

- An ultrasound to determine whether the spleen or liver are enlarged

- A CT scan to accurately visualize the cancer in the body.

How is it treated?

Lymphoplasmacytic lymphomas are usually treated with the following therapies:

- Chemotherapy: The most common medications include chlorambucil, fludarabine and combination chemotherapies, such as CVP chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, vincristine and prednisone).

- Surgery: Surgery for lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma may involve removal of an enlarged spleen.

- Monoclonal antibody therapy with agents like rituximab (Rituxan®) that specifically target and destroy cancerous B-cells. Rituxan® can be used alone or in combination with chemotherapy.

- Plasma exchange/plasmapheresis: This is a procedure specifically for the hyperviscosity (thickening of the blood) associated with this disease. It may be used to thin out the blood when high levels of IgM antibody cause increased thickness.

T-cell Lymphomas

Precursor T-cell Lymphomas

Precursor T-cell Lymphoblastic Leukemia/Lymphoma

What is it?

- A precursor T-cell, called a T-cell lymphoblast, is an immature lymphocyte that is eventually destined to become a mature T-cell. It is this cell that becomes cancerous in precursor T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma.

- Precursor T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma is a type of aggressive NHL that occurs mainly in children and adolescents, with the majority of patients being male. A second peak of occurrence is seen later in life in patients over 40 years of age.

- Lymphoblastic cancers are classified as either lymphoblastic leukemias (called acute lymphoblastic leukemia or ALL) or lymphoblastic lymphomas. Both are cancers of immature lymphocytes with the major differences illustrated in the following table:

Lymphoblastic Leukemia Lymphoblastic Lymphoma Type of lymphocyte most commonly affected B-cells T-cells Where the cancer is located Bloodstream Lymph nodes

What are the symptoms?

- The most common symptoms result from a large mass in the mediastinal area (the centre area of the upper chest), as well as fluid accumulation around the lungs. These symptoms include breathing difficulties and other problems.

- This type of NHL can spread to the central nervous system, and neurological symptoms may also be present at diagnosis.

How is it diagnosed?

- The diagnosis is usually made by lymph node biopsy. A sample of the lymph node is removed and examined under a microscope where it is checked for cancerous cells.

- X-rays, bone marrow biopsy, CT scans and blood tests may also be performed.

How is it treated?

- Intensive chemotherapy is the most common treatment for older children and young adults with aggressive lymphoblastic lymphoma.

- Young patients whose disease is well localized have an excellent prognosis.

- Adults with later stage precursor T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma are often offered stem-cell transplantation as part of their initial treatment plan.

Mature T-cell Lymphomas

Adult T-cell Leukemia/Lymphoma

What is it?

- Adult T-cell lymphoma is an aggressive type of T-cell lymphoma where the cancerous T-cells are found in the peripheral circulating blood.

- Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma is rare in North America and is more common in countries such as Japan and China where a viral infection called HTLV-1 infection is more common. HTLV-1 infection can make people more likely to develop this type of T-cell lymphoma.

- This type of NHL can occur at any age from young adulthood to old age. It occurs slightly more often in men than in women.

What are the symptoms?

- The most common symptoms include swollen, enlarged lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy) and an enlarged liver and spleen (hepatosplenomegaly).

- Upon examination the patient may show signs of skin involvement, high calcium levels in the blood (hypercalcemia), bone involvement and high levels of an enzyme called lactate dehydrogenase (LDH).

How is it diagnosed?

- The diagnosis of adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma is made by lymph node biopsy. A sample of the lymph node is removed and examined under a microscope where it is checked for cancerous cells.

- X-rays, bone marrow biopsy, CT scans and blood tests may also be performed.

- The presence of HTLV-1 virus must also be established.

How is it treated?

- Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma is treated using combination chemotherapy regimens.

- Some patients can survive for a long time with this cancer.

Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (ALCL): Systemic-Type and Primary Cutaneous-Type

What is it?

- ALCL can occur in two different forms:

- A systemic type, where it exists throughout the body

- A primary cutaneous type, where it occurs only in the skin.

- Anaplastic refers to the appearance of the lymphoma cells, which look quite different from normal lymphocytes.

- Patients with ALCL are typically young, with an average age of 33 years, with 70% of patients being male.

- ALCL systemic-type is an aggressive NHL, whereas the primary cutaneous type follows a more indolent course.

- The cancerous cell in either type of ALCL can be a T-cell, or a cell that is lacking B-cell or T-cell markers (called “null”).

What are the symptoms?

ALCL systemic-type:

- Patients with ALCL systemic-type often have enlarged and swollen lymph nodes, as well as involvement of other organs.

- Systemic symptoms and elevated levels of an enzyme called lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) occur in approximately 50% of patients. Bone marrow and the gastrointestinal tract are rarely involved, but skin involvement is common.

ALCL primary cutaneous-type:

- Patients with ALCL primary cutaneous-type usually have a single lump or ulcerating tumour in the skin. Lymph nodes in the area may also become involved.

- The cells involved in this type of lymphoma have a certain protein on their surface called the CD30 antigen.

- Patients may experience spontaneous remissions with this disease. However, the remissions are inevitably followed by relapses.

- A benign condition that can mimic primary cutaneous ALCL is called lymphomatoid papulosis.

How is it diagnosed?

Both types of ALCL are diagnosed by biopsy of tumour tissue. A sample of the tumour is removed and examined under a microscope. Specific features of the disease are identified and the diagnosis is made.

How is it treated?

ALCL systemic-type:

- Treatment regimens appropriate for other aggressive lymphomas, such as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), are generally utilized in patients with ALCL. They include:

- CHOP chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone), the standard therapy for ALCL systemic-type;

- Other therapies including radiation therapy, stem-cell transplants and steroid therapy.

- With combination chemotherapy, many patients with ALCL will be cured.

ALCL primary cutaneous-type:

As mentioned, spontaneous remission may occur with this condition. If no spontaneous remission occurs the most common treatments include:

- Radiation therapy to the area;

- Surgery to remove the area of skin affected;

- Systemic chemotherapy (used only in patients who have extensive involvement that cannot be treated with localized therapies).

Cutaneous T-cell Lymphoma (CTCL)

What is it?

CTCL is a rare type of NHL caused by cancerous growth of T-cells in the skin. It is most common in adults between 40 and 60 years of age.

There are a few sub-types of CTCL, the most common being:

- Sezary syndrome: A specific type of CTCL where large areas of skin or lymph nodes are affected. Patients with this lymphoma may have redness of the entire skin surface and tumour cells which circulate in the bloodstream. This type of CTCL often follows an aggressive course.

- Mycosis fungoides: This is the general name given to the other types of CTCL when the blood is not affected. It is a type of indolent lymphoma where patients often have several years of eczema-like skin conditions before the diagnosis is finally established. In the early stages of the condition, biopsies may be difficult to interpret and the correct diagnosis can only be made after observing the patient over time. In advanced stages, the lymphoma can spread to lymph nodes and other organs.

What are the symptoms?

- CTCL can manifest as small, raised, red patches on the skin, often on the breasts, buttocks, skin folds and face. These patches often look similar to eczema or psoriasis, and may be associated with hair loss in the affected area.

- Patients in later stages may have ulcerating tumours that appear on the skin.

- Lymph nodes in the affected region may also be involved.

How is it diagnosed?

The diagnosis is made by skin biopsy of the area of affected skin. A small piece of skin is removed from the affected area and examined under a microscope.

How is it treated?

Many therapies are used to treat CTCL. They include:

- PUVA: Also called photochemotherapy, this treatment is used if large areas of skin are affected. PUVA consists of a drug called psoralen plus ultraviolet A (UVA) light. Psoralen makes the skin more sensitive to the healing effects of the UVA light. The treatment is similar to sitting under a sunlamp and may be given several times a week.

- UVB therapy: Ultraviolet B (UVB) light slows the growth of the cancerous cells in the skin. This treatment does not include the use of a drug to make the skin more sensitive. Treatment may be given several times a week.

- Radiation therapy: Local radiation may be used for early-stage CTCL if only one or two small areas of skin are affected. Radiation therapy may also be used to treat the entire surface of the skin if the CTCL is more widespread. This type of radiation treatment is called total skin electron beam treatment. It is only given once and then may be followed up with further PUVA treatments if needed.

- Chemotherapy: Chemotherapy drugs may be applied directly to the skin in the form of an ointment. It is very important that you follow the instructions carefully and only put the cream on at the prescribed times. Intravenous chemotherapy may be used if the CTCL is more advanced.

- Bexarotene (Targretin®): This is a medication that may be used to treat advanced CTCL. It is taken daily in capsule form with food.

- Interferon: Interferon is a protein that occurs naturally in the body and is an important part of a healthy immune system. A synthetic form of interferon can be injected under the skin (subcutaneously) in an attempt to boost the immune response and fight the CTCL.

- Photopheresis: This treatment is used particularly for Sezary syndrome. It involves passing the patient’s blood through a machine where it is exposed to ultraviolet light.

Peripheral T-cell Lymphomas (PTCLs)

What are they?

PTCLs are a group of aggressive NHLs that affect a certain type of T-cell. They account for approximately 7% of all NHL cases.

There are many distinct sub-types of PTCLs. They include:

- Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma: This type of PTCL is quite rare and is often confused with a condition called panniculitis, an inflammation of fatty tissue in the body. The most common symptoms include nodules under the skin (subcutaneous nodules) which can progress to open, inflamed sores. Hemophagocytic syndrome—a serious condition in which there is uncontrolled activation of certain parts of the immune system—is also common in this cancer.

- Hepatosplenic gamma delta T-cell lymphoma: This type of PTCL is a systemic (affecting the entire body) illness that presents with infiltration of the liver, spleen and bone marrow by cancerous T-cells. Usually there are no actual tumours. It is associated with systemic symptoms (e.g., fever, weight loss, night sweats, fatigue) and is quite difficult to diagnose.

- Enteropathy-type intestinal T-cell lymphoma: This type of PTCL is very rare and occurs in patients with untreated gluten-sensitive intestinal disease, called celiac disease. Patients are often in a very weakened state and may have intestinal perforation (an abnormal hole in the wall of the intestine).

- Extranodal T-cell lymphoma, nasal type: This type of PTCL, previously referred to as angiocentric lymphoma, is more common in Asia and South America than in North America and Europe. It most frequently affects the nose and nasal passages but can involve other organs as well. It has an aggressive course, and patients frequently have hemophagocytic syndrome, a serious condition in which there is uncontrolled activation of certain parts of the immune system.

- Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: This is one of the more common sub-types of PTCL, accounting for approximately 20% of all T-cell lymphomas. The most common symptoms include generalized lymphadenopathy (swollen lymph nodes), fever, weight loss, skin rash and high levels of antibodies in the blood.

- PTCL, unspecified: PTCL, unspecified is the most common PTCL subtype in North America. It represents all of the PTCLs not classifiable as a specific subtype. It is evident that this represents a diverse group of diseases for which evidence is lacking a clearer definition. Most patients with PTCL, unspecified present with nodal involvement; however, a number of extranodal sites may also be involved (e.g., liver, bone marrow, intestinal tract, skin).

What are the symptoms?

The symptoms of PTCL are specific to the subtype. Refer to the specific subtype for a description of the most common symptoms.

How are they diagnosed?

- The diagnosis of PTCLs requires a biopsy and thorough examination of the cancerous tissue.

- Other diagnostic tests such as X-rays, bone marrow biopsy, CT scans and blood tests may also be performed.

How are they treated?

- Treatment of PTCLs generally involves combination chemotherapy. Treatment regimens are similar to those used for other aggressive lymphomas and include:

- CHOP chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone)

- Radiation therapy, stem-cell transplants and steroid therapy.

- The response to treatment is not often as effective in PTCLs as it is in DLBCL. As a result, stem-cell transplantation is sometimes considered an early treatment option in appropriate cases.