Biologic Therapies

Biologic therapy (also called biologic response modifier therapy or immunotherapy) uses the body’s immune system to fight the cancer or reduce some of the side effects of other cancer treatments. This may be done by helping to repair healthy cells damaged by the cancer thus helping these healthy cells to control the cancer, or by interfering with cancer cell growth. Terms such as interferons, interleukins, and tumour necrosis factor all refer to biologic therapy and more than one type may be used alone or in combination with chemotherapy or radiation treatment.

Types of biologic therapies include:

- Monoclonal antibody therapy

- Radioimmunotherapy

- Interferons

- Vaccines (under clinical investigation)

- Anti-angiogenesis therapies (under clinical investigation)

- Gene therapies (under clinical investigation).

Monoclonal Antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies are becoming increasingly available and can be effective in fighting very specific types of cancer. A healthy body normally produces antibodies to fight infection. Medical research has allowed us to now duplicate these antibodies in laboratories; however, instead of attacking germs, these monoclonal antibodies can be programmed to attack lymphoma cells.

The word monoclonal comes from the terms mono (meaning one) and clonal (meaning a clone of). Thus monoclonal antibodies mean antibodies that are all clones of a single cell and they are all identical. This is important because when the body sends them out to hunt for cancer cells they all behave the same way.

Monoclonal Antibody Therapy

The development of monoclonal antibodies has been one of the most significant advances in the treatment of NHL. Monoclonal antibodies are a more specific therapy than chemotherapy, meaning that they are directed at a target that is primarily located on tumour cells, as opposed to normal body cells. Not only does this make for very effective cancer treatment, it also greatly minimizes the side effects, as normal cells are minimally affected. A monoclonal antibody can be compared to a guided missile that identifies an exact target and kills it.

Monoclonal antibodies come in various different types. Currently in Canada, rituximab (Rituxan®), ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin®) and tositumomab (Bexxar®) are monoclonal antibodies approved to treat NHL. Others are under investigation.

Rituximab, for example, is a chimeric antibody which means it is part mouse and part human antibody. Murine monoclonal antibodies are fully mouse derived. Humanized antibodies are ones that were part mouse to start with, but have been fully converted to human. Then there are fully human antibodies which were entirely human from the start. There is also research being done into primatized (ape) antibodies.

How do Monoclonal Antibodies Work?

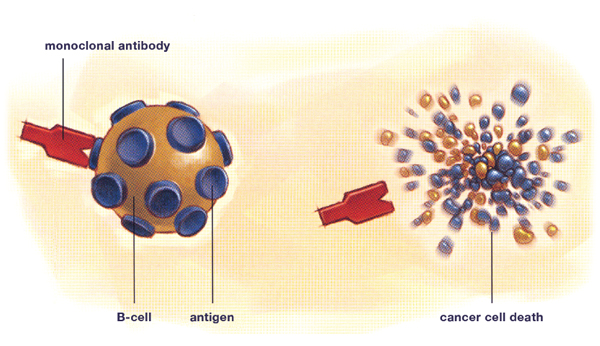

All cells have certain protein markers on their surface called antigens. Monoclonal antibodies are specifically manufactured in a laboratory to recognize one type of antigen. For NHL, the monoclonal antibodies are specifically targeted to antigens found on lymphocytes, the normal body cell that lymphomas are derived from. The attachment of the monoclonal antibody to its target antigen triggers the cell to destroy itself and signals to the body’s immune system to attack and kill the cancer cell.

The most common antigen that they seek is called CD20. CD20 is found on most lymphoma B-cells and on many normal B-cells as well. This makes it an ideal target for an antibody-based treatment. However there is also a lot of research happening using monoclonal antibodies that target the CD22, CD30, CD40, CD52 and CD80 antigens.

Rituximab is a commonly used treatment for patients with either indolent or aggressive NHL. It is used on its own or in combination with chemotherapy and has been shown to increase the length of remission in indolent (slow-growing) NHL. It can also increase a patient’s chance of cure in aggressive (fast-growing) NHL.

Alemtuzumab (Campath®) targets CD52, a protein present on the surface of mature lymphocytes but not on the stem cells from which these lymphocytes were derived. It is used in patients with CLL.

Monoclonal antibodies can also be combined with radiation therapy which delivers a dose of radiation directly to the lymphoma cell. These are called radioimmunotherapies and are discussed in the section titled Radioimmunotherapy.

Rituximab (Rituxan®)

Rituximab is a monoclonal antibody that tightly attaches itself to the CD20 antigen on the surface of B-cells, the cancerous cell in many types of NHL. The CD20 antigen is also present on the surface of healthy, non-cancerous B-cells, which means that rituximab will also attach to and facilitate the destruction of these cells. However, normal B-cells, like all blood cells, are produced in the bone marrow from stem cells, and the stem cells do not have the CD20 antigen, meaning that they are not affected by monoclonal antibodies and are not destroyed. Stem cells can then replenish the store of healthy B-cells in the body. So although during treatment with rituximab the number of mature, normal B-cells is temporarily reduced, their levels return to normal once the treatment is completed. Rituximab is a commonly used treatment for patients with either indolent or aggressive NHL. It is used on its own or in combination with chemotherapy and has been shown to increase the length of remission in indolent (slow-growing) NHL. It can also increase a patient’s chance of cure in aggressive (fast-growing) NHL.

Monoclonal antibodies can also be combined with radiation therapy which delivers a dose of radiation directly to the lymphoma cell. These are called radioimmunotherapies and are discussed in the section titled Radioimmunotherapy.

Monoclonal antibody therapy

How are Monoclonal Antibodies Given?

Rituximab is given intravenously and can be given alone or in combination with chemotherapy, often increasing the effectiveness of chemotherapy treatments while alemtuzumab (Campath®) is given alone (monotherapy). Medications to prevent side effects are given prior to the monoclonal antibody treatment. If side effects occur the treatment can be given at a slower infusion rate or stopped until the side effects pass.

When given on its own rituximab is usually given as four weekly treatments over a 22-day period. When given in combination with chemotherapy, one dose of rituximab is administered with each cycle of treatment (typically eight cycles).

Alemtuzumab infusions generally take two hours. The first few doses are usually given in a dose-escalation format, until the recommended dose is reached. For example, the first day of treatment you are given a very low dose. If you do not have any serious side effects, you will be given a slightly higher dose the following day. Most patients are able to reach the recommended dose in three to seven days. Once you have reached the recommended dose, the schedule for treatment is every other day, three days per week. You can receive this treatment for up to 12 weeks, as long as the cancer cells continue to respond to this therapy and you are tolerating any side effects.

Rituximab Maintenance Therapy

Prolonged treatment with rituximab, called rituximab maintenance therapy, is used to treat patients with follicular NHL who have responded to their initial treatment. This means that patients who have received treatment for follicular lymphoma and have achieved remission (complete or partial remission) may benefit from prolonged administration with rituximab (generally administered every three months for a period of two years). Rituximab maintenance therapy has been shown to sustain the response obtained from the initial therapy and may improve survival for patients with follicular lymphoma. Ask your doctor for more information about rituximab maintenance therapy.

Are There Side Effects from Monoclonal Antibody Therapy?

Unlike the side effects associated with chemotherapy and radiation, most of the side effects from monoclonal antibody treatment are minor and short-lived, lasting only during the actual treatment and for a few hours afterwards. The chances of experiencing side effects also decrease with each treatment received because the patient adjusts to the treatment and, as treatment continues, there are fewer lymphoma cells to kill. The most common side effects are flu-like symptoms including fever, chills and sweating. Less common side effects include nausea, vomiting, rashes, fatigue, headache, wheezing, infection, and a sensation of tongue or throat swelling. Patients are monitored throughout the treatment session for signs of allergic reactions including itching, rashes, wheezing and swelling. If these symptoms occur, the treatment is slowed down or stopped for a short time until the symptoms subside. Antihistamines (e.g., Benadryl®) and acetaminophen are commonly given before treatment to avoid allergic reactions.

Radioimmunotherapy

Radioimmunotherapy uses both radiation therapy and monoclonal antibody therapy to fight lymphoma. A radioactive molecule (a molecule that emits radiation and is capable of killing cancer cells) is attached to a monoclonal antibody so that the radiation is delivered specifically to lymphoma cells. It uses the effective targeting mechanism of the monoclonal antibody and the cancer-killing effect of radiation. This has the benefit of delivering deadly radiation to the cells near the antibody even if there is no antibody attached to it.

Two radioimmunotherapy agents are currently available in Canada for the treatment of NHL. These agents, called ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin®) and tositumomab (Bexxar®), target the CD20 antigen on B-cells. They are commonly given to patients with relapsed indolent NHL who are no longer responding to conventional chemotherapy or monoclonal antibody treatment with rituximab.

How does Radioimmunotherapy Work?

Radioimmunotherapy uses monoclonal antibodies that have radioactive materials attached to them. These radioactive monoclonal antibodies circulate in the body until they find their target—the CD20 antigen of the B-cell (a protein found specifically on B-cells)—and attach themselves there. Once attached, the radiation kills the cancerous B-cell as well as any other lymphoma cells that are nearby.

How are Radioimmunotherapies Given?

Radioimmunotherapies are administered intravenously in the nuclear medicine clinic at the hospital under the supervision of a doctor who is specially trained and experienced with the safe use and handling of radioisotopes. A nurse or technician will assist the doctor and stay with you during treatment.

Other treatment team members may include:

- Treatment team hematologist: A doctor who specializes in diseases of the blood, like NHL.

- Oncologist: A doctor who specializes in treating cancer.

- Oncology nurse: A specialist who will teach you about treatment and assist with your care.

- Nuclear medicine physician: A doctor trained in radiation therapy who will decide your individual dose of the radioactive part of treatment. The nuclear medicine physician may also serve as the radiation safety officer for the treatment centre.

- Nuclear medicine technologist: A specialist who assists the nuclear medicine physician. This person may administer the radioactive part of therapy and perform the imaging procedures.

- Radiation oncologist: A doctor who uses radiation to treat cancer.

- Hospital pharmacist: A pharmacy specialist who may prepare the non-radioactive part of treatment.

- Radiopharmacist: The specialist who prepares the radioactive antibody.

- Radiation safety officer: An official at the hospital or treatment centre who knows the rules for using radioactive substances. This person will also decide if you will be able to go home right after treatment.

What are the Benefits of Using Radioimmunotherapy to Treat NHL?

Possible benefits of radioimmunotherapy for NHL include:

- Enhanced antitumour activity that may result from the targeted delivery of radioactive particles to the surface of cancer cells. This activity is in addition to other mechanisms of action that the monoclonal antibody may possess, such as interactions with the immune system and the induction of apoptosis;

- Radiolabelled monoclonal antibodies can deliver radiation to neighbouring cells in a tumour through a cross-fire effect. This may kill adjacent tumour cells that are antigen negative (i.e., to which the monoclonal antibodies cannot bind) or to which the monoclonal antibodies have not penetrated.

What Side Effects are Associated with Radioimmunotherapy?

There are some side effects from radioimmunotherapy that you may want to discuss with your doctor. These include anemia (low red blood cell counts), thrombocytopenia (low platelet counts) and immunosuppression (decreased immune function, a condition which could leave you at increased risk of infection). Other common side effects include chills, fever, nausea and throat irritation. As with any radiation treatment, there are increased long-term risks of certain cancers.

It may be necessary to speak with a doctor about safety precautions following radioimmunotherapy, as a small amount of radiation may be present in the body, i.e., in the blood and urine, for a short period after treatment. These precautions may include washing hands thoroughly after urination and using a condom during sexual intercourse. Flushing the toilet twice after going to the washroom is also a good idea.

Your cancer care team can determine if radioimmunotherapy is the right treatment for you.

Who is a Candidate for Radioimmunotherapy?

Your doctor will consider many factors to determine if you are a candidate for treatment. These include the specific type of lymphoma that you have as well as several considerations that are important to help minimize potential risks of therapy. Factors such as what kind of lymphoma therapy you have received before, the percentage of lymphoma cells in your bone marrow, your blood cell counts and possible allergies or sensitivities that you may have to any component of the regimen are all important in the decision process.

Ibritumomab Tiuxetan (Zevalin®)

How is Ibritumomab Tiuxetan Administered?

The ibritumomab tiuxetan regimen, consisting of two pre-doses of rituximab followed by one dose of ibritumomab tiuxetan, is delivered over the course of eight days. Since imaging scans are not required to determine the right dose for you, ibritumomab tiuxetan treatment is completed in only two hospital visits on an outpatient basis.

On the first day, you will first receive an intravenous infusion of rituximab, which takes a few hours. Rituximab is given to allow ibritumomab tiuxetan to improve targeting of cancer cells.

On the eighth day after the initial visit, you will return for a second infusion of rituximab, followed by ibritumomab tiuxetan, which is administered by an intravenous infusion that is completed in about 10 minutes. A nurse or technician will stay with you during treatment.

What Precautions are Necessary after Receiving Ibritumomab Tiuxetan?

You should speak with your physician about safety precautions and any questions or concerns that you may have. Ibritumomab tiuxetan emits pure beta radiation, which does not penetrate outside the body. In addition, following treatment you will need to follow minimal radiation safety precautions. A small amount of radiation may be present for approximately up to one week following treatment in the blood and urine. Therefore, it is advisable to observe safety precautions for up to one week after treatment.

Typically, isolation is not required, and it is not necessary to avoid contact with family, friends or

co-workers during this time. There is no special radiation protection required in your home or workplace. You can usually return to work and your normal activities following treatment, and there are no restrictions for travelling. Your physician will provide additional instructions and recommendations.

Safety precautions to be followed for seven days:

- Wash your hands thoroughly after using the bathroom.

- Use a condom during sexual intercourse to avoid transfer of bodily fluids. Men who have been given ibritumomab tiuxetan and who could become fathers must use reliable contraception during and for a year after stopping treatment.

- Pregnancy precautions: Women should use reliable contraception. Pregnancy should be ruled out before you start treatment and should be avoided during treatment and for a year after treatment.

- Breastfeeding women: Talk to your doctor before starting breastfeeding and after the end of treatment, as antibodies are excreted in human milk.

What Side Effects are Associated with Ibritumomab Tiuxetan?

Because the ibritumomab tiuxetan regimen involves the administration of rituximab, side effects of rituximab and ibritumomab tiuxetan need to be discussed. The most common side effects reported by patients during treatment with ibritumomab tiuxetan are mild flu-like symptoms, similar to those reported with rituximab. These temporary side effects include weakness, abdominal and back pain, shortness of breath, chills, fever, throat irritation, increased cough, headache, nausea, vomiting, dizziness and rash.

It is important that you report to your physician immediately all symptoms experienced while receiving rituximab or ibritumomab tiuxetan, as it is possible that there may be indications of potentially more serious side effects. In rare cases, severe allergic reactions to rituximab have occurred.

Tositumomab (Bexxar®)

How does Tositumomab Work?

Tositumomab is considered a dual-action treatment for NHL because it attacks cancer cells in two ways, providing both radiation therapy and biologic therapy in a single treatment. The biologic therapy action is provided by the monoclonal antibody called tositumomab. Tositumomab seeks out and attaches to the CD20 antigen on the surface of NHL cells. The radiation therapy action of tositumomab comes from a radioactive substance, called an isotope, which is attached to the monoclonal antibody. The isotope is iodine-131.

First, tositumomab, with iodine-131 attached to it, finds and binds to lymphoma cells. The monoclonal antibody causes your body’s natural defences to attack the cancer cells. When tositumomab binds to the cancer cells, iodine-131 releases radiation that kills the attached cells as well as other cells nearby.

The monoclonal antibody tositumomab attaches itself to the CD20 antigen. Tositumomab is designed to fit with the CD20 antigen, like a key fits a lock. This type of targeted treatment brings the cell-killing power of radiation from iodine-131 to the NHL tumour. Because the isotope is attached to tositumomab, it delivers radiation directly to cancer cells.

What Happens During Treatment?

Tositumomab is administered in a hospital or treatment centre for four visits over one to two weeks. It is usually given on an outpatient basis. However, depending on the total amount of radiation delivered, the radiation safety regulations in your province/hospital, and your individual home situation, it may be necessary to admit you to the hospital for two to three days.

Tositumomab is given in two steps. The first step is called the dosimetric step, and the second is called the therapeutic step. In the dosimetric step, your nuclear medicine physician or radiation oncologist determines the amount of radiation that is right for you. It involves three visits to the hospital or treatment centre.

How is Tositumomab Administered?

Before you are given any part of tositumomab therapy, your treatment team will give you medicine to help control some of the side effects of tositumomab that may occur with the infusions. Those medicines are called premedications, and they will include:

- Acetaminophen (e.g., Tylenol®) to control fever;

- Diphenhydramine (e.g., Benadryl®) to help with allergic reactions or flu-like symptoms.

Next, you will be given a dose of tositumomab without any radiation. This will be an intravenous infusion that will take approximately one hour. You will then be given the dosimetric dose, which is tositumomab plus a small amount of iodine-131. This infusion will take about 20 minutes. After you receive the dosimetric dose, your nuclear medicine team will take a scan with a gamma camera. This will be completed before you urinate, so be sure to urinate before the first infusion is started. The scan should take less than 10 minutes.

Your nuclear medicine team will use this information to determine how fast the radioactive substance leaves your body (the rate is different for every person). At the same time, the nuclear medicine physician or radiation oncologist will take a camera image to observe where the radioactivity is going in your body.

During infusions, your treatment team will monitor your blood pressure, heart rate, breathing, and temperature. If changes occur, your treatment team may decide to slow down or stop the infusion. Tositumomab may cause reactions because it contains proteins not usually found in your body. After you complete treatment and go home, be sure to call your oncologist or hematologist if any side effects get worse, or if you have any new side effects from the tositumomab treatment.

Protecting your Thyroid

Your thyroid gland produces chemicals your body needs to function properly. To do so, your thyroid absorbs iodine from your blood stream. Because the isotope in tositumomab is a radioactive form of iodine, it’s important to protect your thyroid from absorbing it. Your doctor will give you a thyroid protection medication in pill or liquid form. You must take the first dose 24 hours before your first visit. You will not be able to be treated with tositumomab if you fail to start taking the thyroid protection medication 24 hours prior to the time you are scheduled for treatment. Also, you must keep taking the thyroid protection medication daily during treatment and for two weeks after the last day of treatment. After treatment with tositumomab, you should have your doctor monitor your thyroid function once per year. This requires a simple blood test.

What Side Effects are Associated with Tositumomab?

- Pregnant women should not receive tositumomab. Nursing mothers receiving tositumomab should discontinue breastfeeding.

- Use effective contraceptive methods during treatment and for 12 months afterward.

Radiation Safety

While the iodine-131 in tositumomab is in your body, you will be emitting radiation. Iodine is removed from your body by the kidneys, so most of the radioactivity leaves the body through urine over approximately a week. The healthcare professionals in the nuclear medicine department of the hospital or treatment centre where you’ll be treated with tositumomab are very familiar with iodine-131 and have been trained in radiation safety procedures. They will explain to you the simple instructions that you need to follow after your tositumomab treatment to reduce the risk of radiation exposure to others.

There are three things to remember to help limit the amount of radiation others can receive from you after you’ve been treated with tositumomab:

1. Distance: The farther away you are from other people, the less radiation they will receive from you;

2. Time: The amount of radiation people around you are exposed to depends on the length of time they are near you;

3. Hygiene: Some hygiene (personal care) measures will help make sure the people around you are exposed to as little radiation as possible.

Interferons

Interferon is a protein molecule that is naturally produced by the body’s immune system to help fight infection and kill cancer cells in the body. A synthetic form of interferon has been produced and is used to treat certain kinds of NHL. It is thought that interferon kills tumour cells directly and signals to the rest of the immune system to do the same. Interferon can be given as a maintenance therapy to prolong the remission of patients previously treated with chemotherapy.

Flu-like symptoms are the most common side effects from interferon treatment. They include low-grade fever, fatigue, weakness, and muscle and joint aches. Staying well hydrated often helps with these side effects, as do non-prescription pain medications if recommended by your doctor. Interferon therapy can sometimes cause severe depression. Tell your doctor if you are feeling depressed. Less common side effects with interferon therapy include loss of appetite, aversion to food and a decrease in thyroid function. Due to the large number of associated side effects and the array of newer treatment options, interferon is rarely used in the management of NHL. This therapy is used however to treat T-cell lymphomas.

Vaccines

We are all familiar with standard vaccines for diseases such as polio and tetanus. Vaccines work by injecting an inactive portion of a disease molecule, too weak to cause the disease but strong enough to stimulate antibody production. Upon future exposure to the same disease, the body will be ready to mount a strong attack against it.

Vaccines are currently being studied as a potential treatment for lymphoma but are not yet approved for use. These vaccines are custom-made from each person’s unique tumour. A small amount of a patient’s tumour is taken from a lymph node, modified to make it look like a foreign invader (so the patient’s immune system will attack it), and reinjected back into the patient to stimulate antibody production and an immune response. The idea is that the immune system will then attack the tumour and break it down.

It is not yet known how effective these vaccines will be, but they do look promising. A major goal of cancer treatment is the development of therapies that are less toxic than chemotherapy.

Anti-angiogenesis Therapy

Angiogenesis means the development of new blood vessels. Many cancers are able to stimulate angiogenesis causing new blood vessels to form to supply energy and nutrition to the growing tumour. Anti-angiogenesis therapies work to stop the development of new blood vessels and destroy existing abnormal vessels surrounding tumours. The goal is to cut off the fuel supply to growing tumours and facilitate tumour cell death. Anti-angiogenesis therapies are currently under investigation in the therapy of lymphoma.

Gene Therapy

The main goal of gene therapy is to alter the genetic structure of cancer cells so they can no longer grow, or so they can be recognized by the body’s immune system and destroyed. Other kinds of gene therapies may be able to make cancer cells more vulnerable to chemotherapy and normal cells less vulnerable. This could increase the effectiveness of the chemotherapy but decrease the toxic side effects. Gene therapies are still under investigation but hold promise for future cancer treatments.